The solar industry in India is facing a strange situation. While the Indian Government’s ambitions are growing, and it has some unrealistic targets to achieve, supply chains are crashing under pressure.

Many of you still don’t get what the situation is with solar installation, availability of panels, vendor conditions, and the gap between demand and supply.

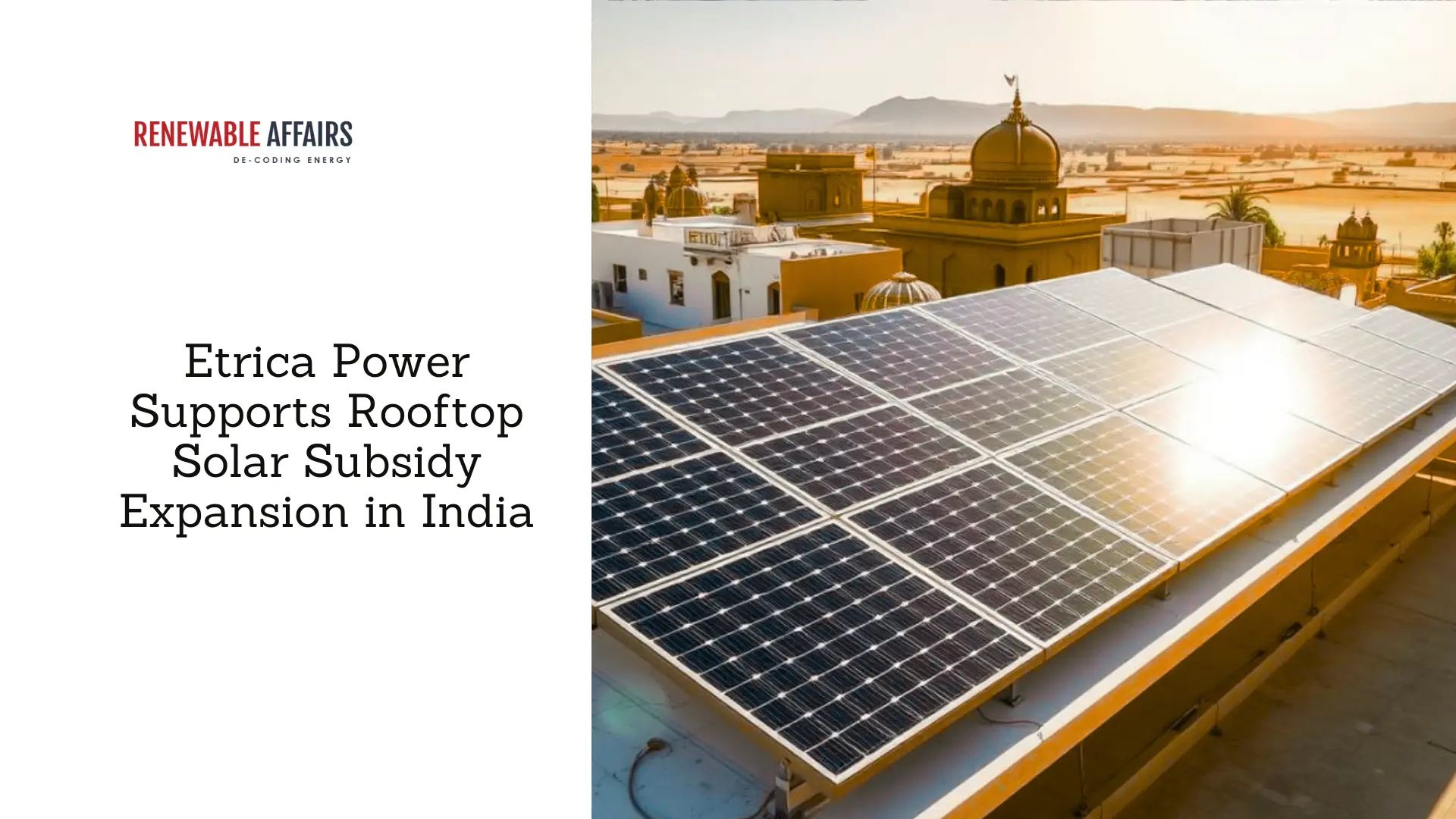

The pressure of compulsion for Domestic Content Requirement (DCR) modules under schemes like PM Surya Ghar Muft Bijli Yojana has exposed deep structural gaps. If the rooftop revolution is to succeed in India, clarity, right direction, and deployment are the basic pillars.

DCR vs Non-DCR: The Real Difference

DCR modules simply stand for using solar cells and panels made entirely in India. MNRE issues a notice for the strict implementation of DCR modules in every installation under PMSGY.

On the other hand, non-DCR modules often use imported cells or panels. These modules are often assembled by cheaper Chinese imports and are available at almost half the cost.

The goal is clear: DCR promotes domestic manufacturing. But the reality is harsh and far more to achieve due to expensive inputs and fragile supply chains. In a price-sensitive market like India, this gap cannot be ignored.

Why the Government Blocks Non-DCR Modules

Now the question is, if the Indian manufacturers are not able to fulfill the current demand of the industry, why government impose blocks on Non-DCR modules?

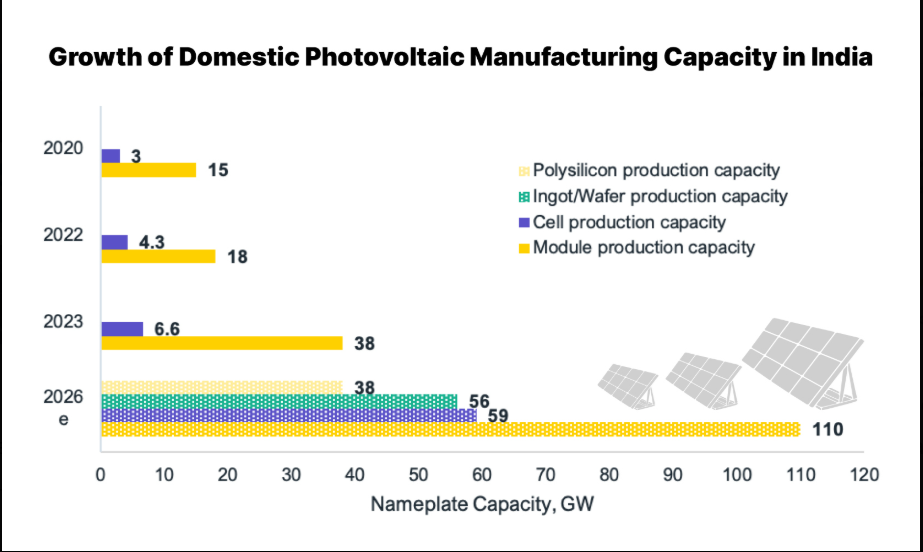

The restriction is rooted in strategy, and India wants to reduce dependence on Chinese imports and build its own solar empire. India’s DCR-compliant manufacturing capacity is only about 50–55% of its total module capacity, as cell manufacturing is much lower than its module production.

Do you think, as a direct stakeholder of the solar ecosystem this can ever be an ideal situation?

Policymakers believe that forcing DCR usage will empower Indian manufacturing. However, this policy overlooks immediate realities and repercussions. The domestic supply chain isn’t ready yet for this big shift. “The intent is nationalistic, but the execution is chaotic.”

Why India Struggles to Fully Assemble DCR Modules

India does not yet have a fully integrated solar manufacturing ecosystem. Core inputs like polysilicon, wafers, special gases, and silver paste still come from abroad. Although domestic cell production is improving, it remains costly and collapsed.

Unlike China, where supply chains are vertically integrated, India’s manufacturers have inconsistent networks.

At the surface, India seems ready, with dozens of vendors registered under government schemes, and contracts are being signed. But on the ground, execution is falling apart.

One key reason: most vendors are not actual manufacturers. They’re system integrators or traders and rely on large players for module supply and often lack direct access to raw materials. When those big supplies take a step back, vendors have nothing to deliver, despite being contractually bound.

Second, backward integration is missing. In China, where solar companies control the supply chain end-to-end from polysilicon to finished panels, most Indian firms stop at module assembly.

They often buy cells, glass, EVA sheets, and wafers from others internationally. Any disruption like a duty hike, import delay, or price jump, can shatter the system.

Now again, the question is, “Why aren’t companies focusing on full backward integration?” Because it’s risky, capital-heavy, and slow. Building a wafer or cell facility requires hundreds of crores and long lead times. Most companies prefer to expand module lines, not foundational infrastructure.

Meanwhile, schemes like PM Surya Ghar make DCR mandatory, but without matching supply or support for integrated manufacturing. So manufacturers chase big, secured government orders (like PM-KUSUM or railways) and leave smaller rooftop vendors stranded.

Even those who have enough capacity are unwilling to cater to rooftop vendors regularly. They demand bulk orders or upfront payments. Many MSMEs can’t match that, creating a trust and affordability gap. That results in a market full of registered vendors, signed contracts, and no panels to deliver.

This isn’t a supply problem, it’s a structural failure. A value chain that starts too late and ends too soon.

Stock Holding Causing Higher Price?

There are strong signals that some stockpiling is happening. Large manufacturers and distributors are holding limited inventories, waiting for prices to rise due to shortages. Vendors notice sudden supply disruptions every few weeks, triggering sudden price spikes.

People in the industry say solar panel prices went up by ₹2–2.5/W, which is more than expected. This makes it look like someone might be messing with the supply on purpose. (Source)

Why Big Companies Cannot Fill the Gap

Even India’s biggest solar players cannot bridge the demand-supply mismatch. A lot of their capacity is already tied up under big-ticket government projects like PM-KUSUM. Some others are busy building up new plants, but output is still months away.

Existing manufacturers face challenges with raw material imports, outdated benchmark costs, and pre-booked orders, causing very little space to address rooftop demand. The anti-dumping duty on solar glass from China and Vietnam is decreasing margins, discouraging rapid expansion.

Rising Costs in the Indian Solar Market

- DCR Cell Cost: ₹13.75/W

- Imported Cell Cost: ₹3.75/W

- DCR Module Final Cost: Up to ₹25/W

- Imported Module Final Cost: ₹8–10/W (Source: Mercom India)

Where Do We Go From Here?

Policies built on just aspiration and intuition will now face operational truth. India’s solar dream cannot survive on shortages and inflated costs.

The MNRE needs to revise benchmark costs, transparently track module availability, and make supply chains better before imposing any mandates. Otherwise, the vendors, MSMEs, and households will continue to pay the price for a system that promised them clean power but left them in the dark.

Solar power was supposed to light up homes. It should not become a source of frustration.

The industry does not seek shortcuts. Until then, rooftops may remain empty, while warehouses hold everything back until we step out of this paradox and take action.

0 Comments